© 2006 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://danginteresting.com/the-halifax-disaster/

On the morning of December 6, 1917, two passenger trains en route to the port city of Halifax, Nova Scotia were stopped in response to a brief, cryptic telegraph message sent from Halifax station: “Munition ships on fire. Making for Pier 6. Goodbye.” The ship described in the message was the French munitions ship Mont-Blanc, which was adrift in Halifax harbor, burning, and loaded with almost 2,700 tonnes of explosives intended for use in the first world war which was then raging in Europe.

On both sides of the harbor, hundreds of onlookers who were unaware of the danger had gathered on the shores to watch the spectacular fire. The burning ship slowly drifted into the pier on the west side, where its flames spread onto land. The fire department arrived in their first motorized fire engine, and began rolling out the hoses in an attempt to douse the flames, but their efforts proved futile. Within minutes, the Mont-Blanc’s highly explosive cargo of TNT, picric acid, and benzol fuel finally reached a tipping point, and the ship exploded in a ball of fire and energy more powerful than any man-made explosion before it.

The morning had started like so many others, with ships beginning to move in and out of the harbor through the narrows after the antisubmarine nets were opened for the day. The Mont-Blanc, captained by Aimé Le Médec, was entering by way of the right channel at a leisurely four knots when another ship, the Norwegian Relief ship Imo, was spotted approaching from the opposite direction in the path of Mont-Blanc. The Imo was traveling the wrong direction for the channel it was in, and moving at almost seven knots, which was exceeding the speed limit of the harbor. The narrows left little room for maneuvering.

Mont-Blanc blew its whistle once, the standard signal to assert right-of-way, essentially ordering the Imo to move into the proper channel. The Imo’s whistle sang out twice in response, signaling that the Imo’s captain intended to maintain its course. Both captains refused to yield as the whistles blew hurried signals at one another through the morning haze, until at the last minute both captains ordered actions to attempt to avoid collision. The Mont-Blanc turned hard to the left, and the Imo put all engines in full reverse, which caused it to drift towards the center. Imo’s prow struck the starboard side of the other ship, and as the steel hulls scraped across one another, a shower of sparks flew which ignited the vapors from the barrels of benzol fuel on the deck of the Mont-Blanc.

Her crew, aware of the danger posed by their cargo, quickly abandoned ship as the flames rapidly grew, feeding on the benzol. As they rowed to shore they cried warnings at the people gathered there to watch the bright flames and oily black smoke erupting from the Mont-Blanc. But none of the Frenchmen spoke English, so their warnings were not understood.

The people watched as the blazing ship slowly drifted up the shoreline until it came to rest at pier 6, setting the pier’s wooden pilings ablaze. A nearby tugboat, which had earlier dodged the Imo to avoid collision, trained its fire hose on the flames, and attempted to tow the Mont-Blanc away from the pier without success. Fire crews from the city also began to arrive to fight the inferno.

The harbor staff, aware of the ship’s explosive cargo and the danger it posed to the city, attempted to organize an evacuation. Workers in waterfront business were ordered to leave, and the workers for the Intercolonial Railway of Canada were warned away as well. One man, a train dispatcher named Vincent Coleman, realized that two passenger trains were still inbound from Bedford, and returned to the telegraph office to signal Rockingham Station to hold any trains inbound for Halifax. He sent the warning successfully, but it was the last thing he ever did.

At 9:04 AM, after having weathered the inferno for twenty minutes, Mont-Blanc’s massive and unstable cargo finally exploded. The resulting blast was enormous. A cubic mile of air was consumed by the terrific explosion, whose force was sufficient to annihilate the Mont-Blanc and push the sea away, exposing the harbor floor for an instant. An estimated 1,000 people were killed instantly by the blast, which tore buildings to pieces and shattered every window within fifty miles. Flying glass and splintered wood caused numerous gruesome injuries throughout the city as the pressure wave shredded many of the city’s wooden structures. Doors were blasted open, and wood stoves were toppled, touching off fires throughout the city. The intense heat of the explosion caused cyclones around the harbor, wreaking further destruction.

Immediately after the initial blast, the twisted, red-hot remains of the Mont-Blanc began to rain upon Halifax, as well as the city of Dartmouth across the harbor. People blown off their feet by the explosion were soon clinging to whatever they could as a tsunami of water rushed over the shoreline and through the dockyard. The sea was brought to eighteen meters above the high water mark, toppling smokestacks and wrenching buildings from their foundations as a mushroom cloud hung overhead.

Two and a half square kilometers of Halifax was completely flattened by the blast. Many thought that the city had been attacked by Germany, but there was little time to consider the cause of the destruction. Entire city blocks were afire, and countless people were injured or trapped in the rubble. The area of Halifax along the shoreline— what had been known as Richmond— made up the majority of what would soon come to be known as the Devastated Area.

As black, oily soot rained down from the mushroom cloud, survivors found the streets of Halifax were littered with severed arms, legs, heads, and mutilated torsos. A huge number of people had received injuries from flying debris and glass, particularly to the face and eyes due to the large number of people who had been watching the fire through their windows. Hospitals were rapidly filled beyond capacity, where doctors began to use triage methods, sending the people with non-life-threatening injuries away from the hospitals to aid stations. Medical facilities were packed so tight that it was difficult to move about, and some battered survivors awoke only to find themselves left for dead in back rooms. Local doctors performed surgeries on their own kitchen tables, using ordinary cotton thread for sutures and their own torn-up shirts for bandaging.

Two American ships which had just left Halifax returned when they saw the explosion and mushroom cloud, and offered the assistance of their medical nurses and orderlies. Firefighters from neighboring cities arrived before nightfall to help in the effort to put out the burning structures, but many of their fire hoses were of different sizes, and unable to connect to the Halifax taps and hydrants.

The rescue effort was not an easy one. Most of the utilities had been knocked out of commission by the blast, and many of the people working to save their fellow citizens were injured themselves. A panic was stirred up after rumors of second impending explosion, sending many rescue workers retreating to higher ground. The second explosion never came, but the distraction was a significant setback to rescue efforts. The following day, the already battered city was hit by a brutal blizzard which caused further complications. But American medical teams began arriving 48 hours after the explosion, offering relief for exhausted doctors, nurses, and rescue workers.

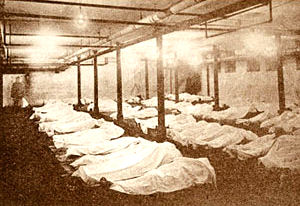

All told, about 2,000 men, women, and children were killed that day, and some 9,000 injured. Makeshift mortuaries were left with the grim duty of processing bodies, which arrived by the dozens. Trains came and went from the city, bringing in men and women to help in the rescue efforts, and hauling away the dead, injured, and homeless. Dartmouth was less hard-hit, but far from spared. Approximately one hundred souls died there, and many of its buildings were damaged by the blast.

On that day, the Halifax explosion was the most powerful explosion that had ever been created by man. As a result of the blast, the Imo was found beached on the Dartmouth shore, lifted there by the massive tidal wave. One of the Mont-Blanc’s cannon barrels was thrown three and a half miles, and her 1/2 ton anchor was later found two miles in the opposite direction. The event would hold the record as the most powerful man-made explosion for the next twenty-eight years, when it was bested by the the first atomic bomb test explosion in 1945.

© 2006 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://danginteresting.com/the-halifax-disaster/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://danginteresting.com/donate ?