© 2008 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://danginteresting.com/the-confederacys-special-agent/

In late 1863, the ongoing War Between the States was not going well for either the Union or the Confederacy. Two years of armed hostility had led to a stalemate, with mounting casualties on both sides. Protests were widespread, some of which even turned into riots. In order to quell opposition and further the war effort, President Lincoln had suspended certain civil liberties. Congress was bitterly divided along party lines, with a significant faction calling for a peaceful settlement. The partisanship had spread to the press and state governments, each side viciously attacking the other. The governor of Indiana went so far as to dissolve the state legislature and run the state as a military dictatorship. The upcoming Presidential election was looking to be a real corker, with the prospects for Lincoln’s re-election looking very dim.

Seeing an opportunity to turn the tide in their favor, Confederate leaders recruited sympathizers and infiltrators to engage upon a campaign of guerrilla warfare. Millions of dollars were set aside to finance the plan, with bonuses to be given to saboteurs in proportion to the damage they wrought. A good portion of those funds was specifically designated for cross-border operations from Canada, where a number of Confederate officers and prominent sympathizers had fled. At the very least, they hoped to cause an uprising of sufficient proportions that some Union troops would have to be redeployed away from the Confederate front. This was the start of what would become known as the Northwest Conspiracy.

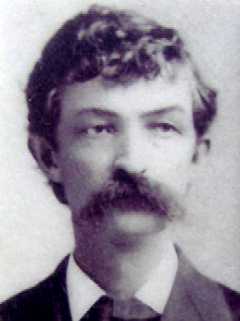

These operations were placed under the command of Captain Thomas Henry Hines, a Kentuckian who had contacts within the pro-South underground networks along the Ohio River. Hines’s mission, which he chose to accept, was to go to Toronto, contact those officers and agents, and carry out “any hostile operation”, provided he did not violate Canadian neutrality. Hines and other Confederate leaders felt that by raising insurrections in those states, they could gain enough influence there to turn them against the Union and bring about a Confederate victory.

Although he was only in his twenties, Hines certainly had experience in dangerous undercover operations. Under the command of Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan, Hines had participated in raids by leading a unit of Confederate soldiers disguised as Union troops who were looking for deserters. When discovered, he fled by swimming across the Ohio River under a hail of gunfire. He was reunited with General Morgan a week later, and though the pair were soon captured by Union soldiers, Hines somehow managed to break them both out of the Ohio Penitentiary. Running into Union troops in Tennessee, he also provided a distraction for Morgan that allowed the general to escape while he himself was captured. That didn’t stop the slippery Hines; he regaled his captors with amusing anecdotes until he had the chance to subdue his guard. He then made good his own getaway.

Capt. Hines hoped to take advantage of a “fifth column” of sympathizers, already in place. Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and Michigan had been settled in large part by people from the southern states, many of whom were “Copperheads” with Confederate sympathies. While they may not have been too keen on slavery, they still felt that blacks were inferior to whites, and didn’t care for the arrogance of the New England abolitionists. When war began to seem inevitable, “peace societies” started to form. With names like Knights of the Columbian Star and Sons of Liberty, they grew in popularity. Members underwent rituals and swore oaths, often oblivious to the true nature of the leaders’ subversive and dangerous plans. The Knights of the Golden Circle was one of the largest and most active. In 1861, they were openly recruiting for the Confederate Army in Illinois, and they engaged in gun-running and guerrilla raids in Iowa. By 1862, they were estimated to have as many as 80,000 members.

In the summer of 1864, the conspirators had men and materiel in position and were ready to strike. The armies of the North and South were both stalled in the field, and the Democratic presidential candidate Gen. George McClellan was highly favored to win the election that fall on a peace platform. Hines and his cohorts concocted a grand scheme: They would build a skilled army by attacking Union prisoner-of-war camps and freeing the detained Confederate troops. These tens of thousands of experienced soldiers could then arm themselves by raiding nearby armories. With simultaneous strikes across the northwest, a general uprising was sure to follow.

Their first planned action was to attack Camp Douglas, a poorly-guarded prisoner-of-war camp in Chicago. For maximum psychological effect, the raid was scheduled to coincide with the Democratic National Convention in late August, 1864. Under normal circumstances, it would not have been difficult to add the thousands of soldiers to the Confederate cause, however the city’s defenses were reinforced for the convention. With a victory by McClellan in the presidential election seemingly guaranteed, most of Hines’ potential recruits didn’t want to risk life or limb, and he was unable to secure enough volunteers. Hines could talk his way out of trouble, but he couldn’t talk others into it.

All was not lost; the conspirators also planned a nearly identical and simultaneous assault in Indianapolis. The Union received word of the plot from Felix Stidger, a Union counterspy who had once held the office of Grand Secretary of the Sons of Liberty. Union Col. Henry Carrington arranged for a dramatic midnight sweep, arresting five leading conspirators. When Indiana judges handed down death sentences for two of the prisoners, there were riotous rumblings among the citizenry. Confederate supporters answered a call to arms, and began to conduct military drills. Col. Carrington, Governor Morton, and other Indiana officials wrote to Washington DC warning that the state was on the brink of chaos. At the eleventh hour, President Lincoln intervened and commuted their sentences to life imprisonment.

A few weeks later, the Conspiracy was dealt a severe blow when Union forces penetrated Confederate lines in Georgia and seized Atlanta. With a Union victory and Lincoln’s re-election now seemingly inevitable, time and money were both running short. The Conspirators were forced to turn to drastic actions.

On September 19, 1864, John Yates Beall led a group of plotters onto the Lake Erie steamer Philo Parsons in Detroit as ordinary passengers. Beall persuaded the captain to make an unscheduled stop at a town in Canada, where more of his conspirators boarded, smuggling aboard weapons and other equipment. The raiders’ target was the USS Michigan, the linchpin of the Union’s defense of Lake Erie, and the only serious military obstacle between the conspirators and the POW camp on Johnson’s Island. If the conspirators could take the Michigan, it would be a simple matter to liberate the prisoners, raid the armory, and use the resulting army to beleaguer Union forces in Ohio. As the Philo Parsons neared Johnson’s Island, Beall put a gun to the helmsman’s head, and ordered that everyone but his own men be put ashore. Beall then steamed his prize to a point off Johnson’s Island to await a signal from the Michigan, where a fellow plotter had befriended the captain. Unbeknownst to Beall, however, the agent aboard the Michigan had been discovered and arrested, and had spilt every bean. After a prolonged wait with no signal from the Michigan, Beall was forced to abandon the plan amidst murmurs of mutiny. He set course for Canada, landed everyone ashore, and then burned the Philo Parsons.

In October the conspirators tried again. About 20 of Hines’ agents sneaked over the Canadian border into St Albans, Vermont, intent upon plundering and burning the village in “retribution” for Union wrongdoings. On October 19, they staged a simultaneous robbery of the town’s three banks. They jayhawked over $200,000 before fleeing back to Canada, but a woodshed was the only casualty in their effort to torch the city . Canadian authorities were able to arrest most of the raiders, but the Canadian court ruled that they were “legitimate military belligerents” and ordered their release without extraditing them to the Union. The loot they had on them when they were captured was returned to St. Albans.

One opportunity remained to inspire an anti-Union uprising in the northern states. Even as the Confederacy was collapsing, Hines rallied his forces one last time to take Camp Douglas in Chicago. It was to be a surprise attack under the cover of darkness, with Conspiracy agents tasked to cut the telegraph wires and burn the railroad depots. The liberated prisoners of war would then take possession of the city, seize the banks, and “commence a campaign for the release of other prisoners of war in the States of Illinois and Indiana, thus organizing an army to effect and give success to the general uprising so long contemplated by the Sons of Liberty.” The assault was scheduled for Election Day, November 8, 1864.

In the days leading up to the attack, the plotters assembled men and munitions, compiling a sizable cache of resources. Hines’ well-armed militia of over 100 “bushwhackers, guerrillas, and rebel soldiers” stood a very good chance of overwhelming the defenses of Camp Douglas, and the release of the 10,000 or so Confederate prisoners would be a force to be reckoned with. On the night before the raid, however, Hines and his co-conspirators were paid an unexpected visit by the commander of Camp Douglas: Col. Benjamin J. Sweet. He was accompanied by a posse of Union Army agents. Having been tipped off by suspicious activities and rumors, Sweet foiled the plot just before it could spring into action. He seized the cache of weapons and used it to reinforce the Chicago’s military guard, thereby ensuring the city’s safety. The raid’s leaders and several Sons of Liberty officers were arrested, though Hines— the mastermind of the conspiracy— was nowhere to be found. He turned up outside of Chicago sometime later, allegedly having evaded capture by hiding inside a mattress.

A few more desultory attempts were made. An attempt to put New York City to the torch started some twenty fires, but they were quickly controlled and there was no resulting panic or uprising. John Beall tried derailing Union trains near Buffalo, NY. All three of his attempts failed. The Conspiracy’s last gasp was thwarted by an alert U.S. Consul in Bermuda, where doctors were treating an outbreak of yellow fever. The official discovered that a certain doctor from Kentucky had been secretly shipping the victims’ blankets and clothing to conspirators in Canada. The scheme was to ship the contaminated goods back into the northern U.S. in the hopes of starting an epidemic. Even if that plan had been carried out, the intended victims had nothing to fear: yellow fever is spread through mosquito bites, not contaminated clothing.

By April 1865, the War Between the States was over. President Johnson continued Lincoln’s policies of reconciliation, and in the following month, offered a wide-ranging amnesty to all but high-ranking officers of the Confederate forces. By simply swearing an oath of allegiance to the United States, they would be forgiven of their rebellious activities. Hines, who was biding his time in Canada by studying law, accepted the offer. He returned to his native Kentucky, where he soon opened a law practice in Bowling Green. He ended his career by serving two terms as the Chief Justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals. He died in January of 1898.

Because it was technically unsuccessful, the story of Captain Hines and the Northwest Conspiracy is often overlooked in discussions of the American Civil War. Most modern historians blame the organization’s failure on Hines’ overestimation of the Sons of Liberty and their comrades-in-arms; it turned out that these rabble-rousers were all talk, with very little inclination for significant action. Hines also consistently underestimated his enemy’s intelligence-gathering abilities, which allowed the Union Army to hamper many of his schemes before he could carry them out. Nevertheless, Hines and his co-conspirators came very close to influencing the course of the war on several occasions, and might have done so were it not for the sharp eyes and good fortune of a few men of the Union Army.

© 2008 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://danginteresting.com/the-confederacys-special-agent/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://danginteresting.com/donate ?